Slow-feed hay nets help laminitic horses

These are two slow-feed hay nets sent to me by a reader named Angie. They are put together quite professionally.

I avoided the slow-feed hay net trend for a long time because my gelding, Kurt, has a history of putting his front feet where they don’t belong. I was convinced I’d come home from work to find him hanging from the wall.

One of my readers, Angie, convinced me that Kurt couldn’t get his foot through the slow-feed nets, and she sent me two that she made from hockey netting. She also showed me a video of her horse eating from a similar net. In the video, the horse shakes the net to drop some hay on the ground and then cleans it up before repeating the process. And his weight looks absolutely perfect.

After seeing that, I was on board. Angie mentioned that I might need to put some hay on the ground even while putting some in the nets until the horses got used to eating that way, so I did.

Kurt caught on to the slow-feed nets right away. Robin thought they were too much work. Eventually, Kurt soured on them, too, and the hay in the nets didn’t get eaten.

I asked Angie if I could cut some diamonds out of the nets to create bigger holes. That worked. The horses started eating the hay again. But it allowed the horses to pull out a lot more hay than they could from the original mesh. We needed a happy medium.

I thought I’d try larger mesh.

Thus, began my education on sports netting. There’s a lot of sports netting out there.

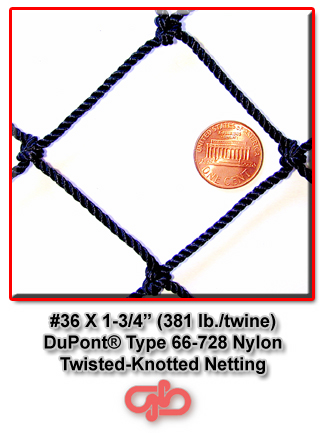

Angie’s netting appears to be 1 1/4-inch mesh. A penny almost fills the opening.

The best way to judge netting size is with a penny. This is what all the websites use.

Angie’s hockey netting appeared to be about a 1 1/4-inch mesh in a diamond shape. There is also squared-shaped netting.

We thought 3-inch mesh might be better, but no one makes an affordable 3-inch mesh.

We found a 2-inch mesh on the Gourock website, but it was in a square pattern, and I wasn’t sure if a square pattern would be as easy for a horse to eat through; Gourock had a 1 3/4-inch mesh in a diamond pattern, and the website said it stretched. I emailed Gourock to ask if the store had an opinion on which would be better.

This is how Gourock displays its mesh.

Gourock responded that its 1 3/4-inch diamond mesh was a very popular mesh for hay feeders.

Another consideration was knotted or knotless. Knotted sounded like it would be more heavy duty.

I ordered the 1 3/4-inch diamond-shaped knotted netting with a 381-pound breaking strength at 50 cents a square foot. I asked for a width of 60 inches so I could fold the width over, making each hay net 30 inches deep. I’d say 30 inches is almost right for a depth. A few inches shorter would have been better with the stretchy material. I figured my nets would be 2 feet across, so I would need a length of 12 feet for six nets. I ordered a few more feet so I could make mistakes.

I don’t think I ordered the right thing. The mesh size is fine, though the horses still prefer Angie’s nets with the cutout holes to having to pick the hay out of this larger mesh without the holes.

The Gourock rep warned me that the diamond pattern would be harder to work with than a square pattern. Yep, the diamond material is all over the place when you try to cut it. Speaking of which, my tip for cutting diamond-patterned netting is to cut left, then right, then left, then right in zig-zag pattern. If you do that, you will actually cut straight across.

Angie’s seam

I did not order my hay mesh with borders, but that’s an option, and I think the border would have helped tremendously in attaching the sides together. I’m still struggling with this. Angie was able to wrap thin twine around the seams of her nets and make the seams perfect. I have not been able to do that. I’ve tried twice, and I give up. I have been tying knots along the sides with tarred Seine twine in a size 12 that I bought on Amazon. The tar is unnoticeable, if that seems off-putting. It’s suppose to keep the twine secure. Kurt untied some of the knots in my first model; my latest model has somewhat obsessive knotting, and it has survived.

If I were to reorder the netting from Gourock, I would get knotless, 2-inch square netting with borders on the netting, mostly likely the rope border unless I were to take up sewing and would be able to work with the nylon webbing border. The rope border would allow me to create a smooth and more secure seam.

My slow-feed net is black with a pink cord.

For the cord around the top, I used a 3/16-inch twine that I bought at Lowe’s and cut it at a length of 84 inches. I tried 72 inches, but that length didn’t allow me to pull the net as wide as I wanted when I filled it. The extra 12 inches means I have to wrap the cord an extra time around the post I’m using to hang the net, but that’s OK. I used a contrasting color, hot pink, so I’d be able to find the cord better when trying to fill my black netting, but it looks a little tacky. Angie used a white cord with her white netting, and that looks nice.

I used the cheapest snap I could find at Lowe’s. The snap needs to have a snap at one end and a circle at the other. After threading my twine through the snap and making a knot, I wrapped electrical tape below the knot, taping the twine ends to the twine, to secure the knot.

Electrical tape keeps my snap secure.

I am convinced that slow feeder nets are our best asset yet in overcoming the problems with today’s high-calorie and high-sugar hay.

The equine feed class that I took online through the University of Edinburgh recommended these nets, or at least using two of the regular nets, which would put more barriers in the way of the horse.

There are many small net products on the market. One Facebook reader suggested hay pillows, which her horses love, and I think these are really nice. I would say that mesh size is too small for my horses, given their demonstrated laziness, but maybe not, because they could push against the pillow to get the hay out. And the pillows allow the horses to move around to get some exercise.

This is where we come to my first concern about the nets. Once I put them up during the winter and got them adjusted to meet my horses’ approval, the horses didn’t move much. They stood in their shed all day pulling the hay out of the net. That’s not what I want to see happen. I want them moving. And a little less poop in the shed would not be a bad thing.

My second concern, or observation, is that my horses don’t bother eating hay from the nets if the horses are not madly in love with that bale. If I put the same hay on the ground, the horses will pick through it. Since we didn’t have a good hay year last year, not every bale is perfect.

Still, I am a fan. I’m a big fan. I’m kicking myself for being opposed to the idea in the early going.

Thank you, Angie.