New Treatment Method Softens Dry Hooves, May Fight Laminitis

This fall (fall of 2023), I created a successful treatment for softening dry and rock hard hooves, but that may be the least interesting part of the story.

I may have discovered a potential secret to treating laminitic horses.

I now believe fully treating a laminitic foot includes directly treating inflammation in the sole and frog of the hoof — as in, treating the bottom of the foot — in addition to the heat and digital pulse higher in the hoof.

And I have learned that a successful way to treat the bottom of the hoof is making sure the treatment doesn’t get immediately removed by dirt and shavings.

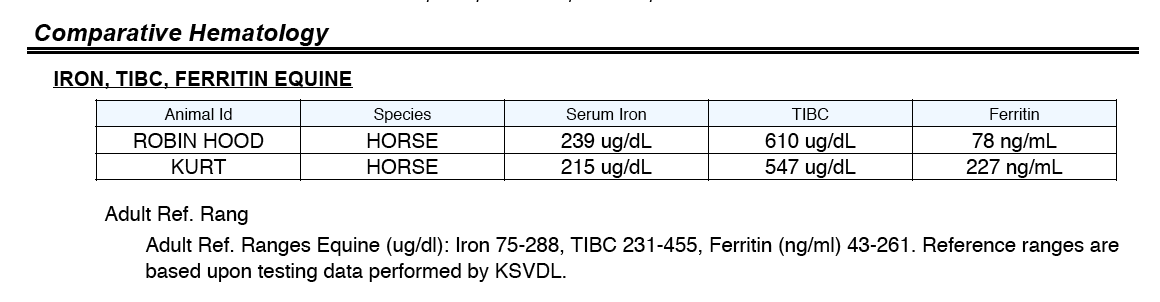

After much experimentation, I wound up concocting a winning cream mixture of regular hand cream, Equate arthritis cream (which is similar to Aspercreme) and Laminil (a mast cell stabilizer; prescription required) to Kurt’s sole and frog.

I held that cream mixture in place with a freezer bag and duct tape for one to four hours, depending on my schedule.

And, bingo. Kurt went from very lame to sound over a few weeks.

Today, Dec. 19, he galloped around his pasture at a pretty fast pace. I have no video. I had a work crew at my house removing a downed tree, and I didn’t want to ask the foreman to stop talking to me so I could go video my horse. But I was tempted. The foreman commented that the galloping Kurt was beautiful. A 28-year-old Connemara pony that everyone wrote off as ready to be put down got called beautiful today when he raced around his pasture. Big victory for us.

My initial search to treat dry hooves

I’ve been searching the internet for “best treatment for dry horse hooves” since 2017 (six years now).

I have never found a satisfactory answer.

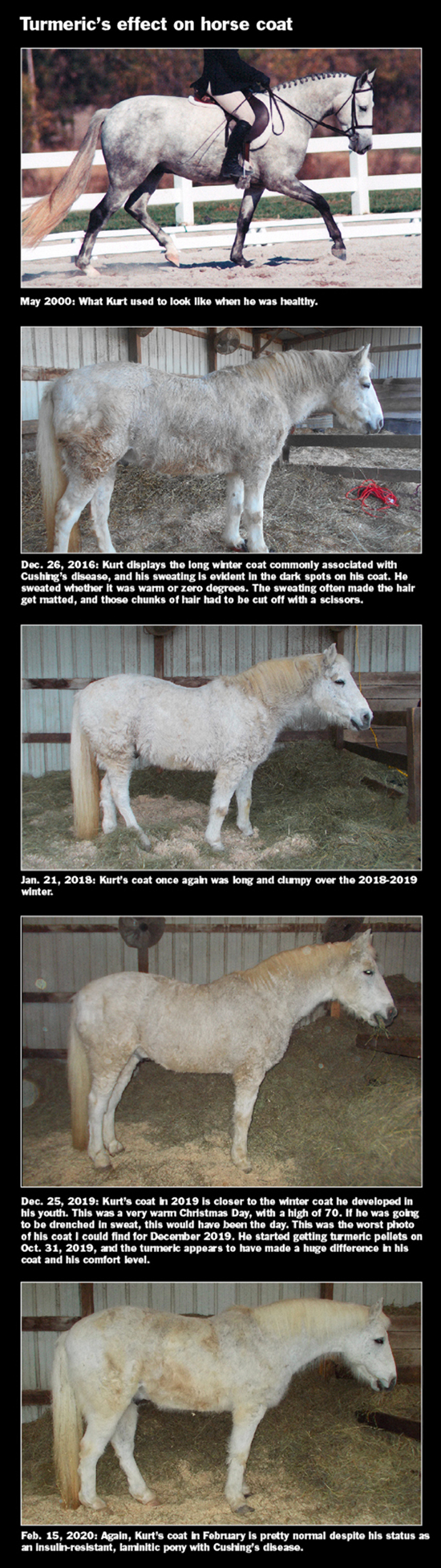

Every fall, Kurt, a chronically laminitic pony since 2010, has suffered from his feet getting too dry, often after I’ve cleared up a frog infection in August.

He goes back and forth between feet too wet and too dry.

I would celebrate solving one problem only to face the other. A frog infection is easier to treat than a dry foot, at least in Kurt.

This hasn’t seemed to be a laminitic episode. He hasn’t had heat or a pulse. I’m guessing that low-grade laminitis is percolating all the time, but the main issue is his feet get too try and don’t have any flexibility. The hooves are rock hard, like walking on a Dutch clog.

I have applied a ton of cream to his feet over the years, including on the sole and frog. It has seemed to make him worse. And that makes sense in hindsight. Nothing is going to make shavings stick to his feet like cream, so I was just encouraging dust to collect on his feet and dry them out.

My first successful experiment in moisturizing Kurt’s feet this year was Sept. 23 when I gave Kurt’s feet a quick soak in plain warm water, then applied cream and covered each foot with a freezer bag secured loosely around his ankle with a piece of duct tape about 18 inches long.

After an hour, Kurt was noticeably better (see video for before and after clips).

But he was less sound the next day. The treatment was a short-term fix.

I redid the treatment every afternoon, he walked around well at night, then he stood in his shavings the next day, and he was back to sore by afternoon.

While I recognized that my timing was wrong — I should have been applying the treatment in the morning, moisturizing his feet during the day while he was in the shavings — I really just wanted to come up with a solution that was more long-lasting.

I started trying to improve the formula, and I dropped soaking his feet when I did, because Kurt and I both hate soaking his feet.

I first added in Equate arthritis cream to the hand cream, targeting pain and potentially inflammation. It’s really cheap ($3.30ish at Walmart). I used maybe a fourth of the tube on two feet.

I saw another big improvement. And the effects lasted a little longer. We were able to skip a day here and there from treatment.

But when I finally started adding in Laminil cream, that was a game changer. Kurt’s walk started getting some bounce and confidence.

I am selling nothing. I say this in every post, but I’ll do it again here. I get nothing for writing anything in this post, and most of these items are probably already in your home.

If you want to see if arthritis cream for a sore foot, or hand cream for a dry foot, is all you need to make your horse’s feet less ouchy, try it and see what happens.

You will be out less than a dollar in ingredients.

Also, I want to point out this works to soften a hoof for a trim. I trim Kurt’s feet, and boy has this helped.

I couldn’t do anything with his rock hard soles all summer. A hoof knife was useless. I could sand them with a belt sander, but even that took work.

Another plus is this is first time since maybe July that Kurt hasn’t been getting sore after I trim him.

I’m pretty excited to have solved this issue for Kurt. He doesn’t mind the freezer bags. He doesn’t seem to notice.

One note: Don’t use comfort boots for this. Wet feet and comfort boots wind up creating ulcers on the horse’s heels. Some soaking boots will work, and we did that for a few days, but I don’t want Kurt destroying his soaking boots walking around. The bags hold up well unless Kurt trots.

Analyzing what we do in general to horses’ feet

Wetness: I see websites that suggest dry feet can be moistened by soaking a horse’s feet for 15 to 30 minutes per day. Does taking a shower every day make a human’s skin more moist? No. It dries out the skin. Same for a horses’ feet unless you add moisturizer afterward and make sure it stays there. Farriers often complain about horses going from wet paddocks to shavings and back again all day, saying that it is a bad combination for creating overly dry hooves.

Shavings: Most horses, especially mine, stand in shavings a lot. Kurt tends to stand in his shavings from 7 a.m. to 7 p.m., though he walks out in his pasture for chunks of time. After 7 p.m., he goes out to graze overnight and stays out most of the night with the exception of a nap around 4 a.m. in his shavings. He picks that schedule. I don’t make him do anything. The shavings are doing what they are supposed to do. It’s just a bit of overkill having a horse stand in moisture-drawing shavings so much.

Dry weather: When it rains now in the Midwest, where we are, it really rains. The rest of the time, it’s really dry. We had a particularly dry year in 2023 (creating a hay shortage in addition to dry hooves). Continuing weather challenges mean my treatment for Kurt’s dry hooves has to be sustainable. I am willing and able to apply cream and bags. It’s not something I dread every day. And Kurt doesn’t run off when I show up with my stuff, even though I don’t halter him and he can run off now.

How long must one keep this up?

I intend to keep applying the cream and bags at least a few times a week until Kurt stops improving.

If I could be so lucky as to have him one more summer, I’d love the chance to test this again in the summer of 2024 during the worst heat and dry weather.

I’ve been so amazed already. I’m pretty confident that I’ll be able to keep him sound.

If this catches on, remember where you heard it first. There are a lot of vets who think I’m crazy. No, I’m just determined. I’d like to take something away from 25-plus years of fighting laminitis 24/7 in six horses. If it’s credit for a freezer bag potion, so be it.